In 2009 the Brisbane City Council asked me to contribute to an anthology they were publishing called One Book Many Brisbanes. I grew up on Tamborine Mountain, a rainforest community in the hinterland of the Gold Coast, about an hour’s drive south of Brisbane, but both of my parents had been born and raised in Brisbane and I’d always considered it the big city to my mountain home. I came to know the place better after I moved there to go to university. I met and married my husband in Brisbane, had three sons there, and by and by a not-insignificant portion of life was passed on the slopes of Paddington; and yet, when I sat down to write my essay, it seems that my mind did not fix on those events, that place: it went back further still. For I have known two Brisbanes in my lifetime and they refuse to merge, both held simultaneously and discrete in my memory. There is the Paddington of my adult life, in which I move with comfort and ease; and there is the Brisbane of my childhood, a strange, shimmering place, where exotic things like grandparents and Christmas windows and council buses belong, where it is always hot and I am an outsider, a mountain kid, observing, admiring, and always taking notes.

If you prefer to listen, rather than to read, you can do so here:

We Were from the Mountains

We were from the mountains and Brisbane was the Big Smoke. We didn’t go often – petrol was expensive and our budget didn’t stretch to joyrides – but at some point, in the long summer holidays, Mum would take my sisters and me to see Nana. ‘A visit to the City,’ we used to call it, and we always wore our best clothes.

Our car was a mustard-coloured Triumph that had brought us from South Australia a few years earlier and we drove with the windows down, bugs flying in with the noises, as rainforest (whip birds, water tumbling over rocks) gave way to the heat of the bush (cicadas, the sound of sunlight stretching) then, finally, the burn of brake pads as we crossed the rickety bridge in the bottom gully – the one that flooded when it rained and turned our mountain into an island.

A quick stop for me to throw up (I never could resist reading in the car) and we were away again, up the Pacific Highway, legs sticking to the vinyl seat, bickering over whose skirt had strayed across whose upholstered line, until Mum, driven mad in the front, would start the competition: who could see the buildings first? And we’d fall silent, until somewhere around Gaza Road when at last the high-rise towers rose into view.

When we finally reached Stafford, Nana would be down the front beneath the Y-shaped frangipani, waiting to pull up the metal rod and swing open the gate. We always parked on the grass in front of the house. People didn’t fill their yard with garden beds then, not in Brisbane, and there was no need for a garage as Nana didn’t drive. This fact seemed amazing and somehow impressive to us, like not being able to swim, or work a video player; it was a choice that marked her immediately as of another age.

Nana was soft and pretty, with papery pale skin and the blue eyes of a young girl. She used an umbrella in the sun, long before it was fashionable, having suffered a fierce burn in her youth. (She’d been twenty years old, the war, which was gathering in the wings, had not yet burst onstage, and when she was invited by friends to take a pleasure cruise along the Brisbane River, she was delighted. The burn took years to heal and Nana never again underestimated the Queensland sun.)

Hers was a Housing Commission home, a good, honest house, she’d say proudly, built with hundreds of others in the spate of postwar optimism which divided Happy Valley into clean, neat blocks holding clean, neat dwellings, intended for clean, neat families. In 1955, the Connelly clan had waved goodbye to the fibro cottage they’d called home on the muddy flats of Cribb Island, and taken up their suburban dream on the slopes of Stafford.

The block climbed away from the street so that the front of the house was high-set while the back cut into the hill, and the house itself had the long, strong legs of a shoreline fisherman. We’d been warned numerous times to be careful on the front balcony and were under strict instructions not to emulate our mum’s childhood game of lowering her baby sister over the edge in a rope-tied basket.

While Nana and Mum shared a pot of tea, my sisters and I headed straight out the screen door into the backyard. There was a huge mango tree against the top fence, with glossy leaves and an embarrassment of fruit, and we’d climb as high as we could, amassing mangoes along the way. From our bower among the branches, we’d peg them at the incinerator, one by one, seeing how many we could bullseye down the chute. We ate them, too, straight off the tree, stringy sun-warmed flesh and juice leaking down our arms. (Once I ate too many and was sick all afternoon in nana’s pink porcelain bathtub.)

Time was different then. The day slowed as the heat thickened, and eventually we would leave the tree to poke about in the external laundry, pretending it was our own cottage in the middle of an enchanted forest. Or a time machine capable of transporting us to a million different locations. The old Hoover washing machine and its wringer were the controls, and the boiler and pine stick poker Nana used to wash sheets became weapons to fend off our adversaries.

Sometimes our enemies were especially wily and we needed the added power of the Hills hoist. We’d wind it as high as it would go, then sprint from the top of the yard and launch ourselves into space. Round and round I flew, muggy breeze on my face, laughter erupting from deep in the pit of my stomach. And, in the yellow-green blur of the yard, I sometimes fancied that I glimpsed three ghostly girls, Mum and her sisters, playing at tightrope on the rim of the fence.

We always made enough noise to bring Nana’s neighbours into their backyards. They were a never-changing cast – people didn’t move as much then, nesting for life rather than shifting with the market. Nana knew when to make her entrance, emerging from the kitchen and shuffling to meet them at the shared fence. We’d be called over for inspection and made to stand on the old cement steps that had been pushed against the wire when the dunny was made defunct. Remarks were passed about how much we’d grown, and Nana would beam. They knew everything about us – awards we’d been given for science projects, ballet exam results, stars on the classroom chart – but we never knew their names.

When the accomplishments of various grandchildren had been compared and all declared gifted (though each woman clung silently to the certainty of her own brood’s superiority), we’d be dispatched once more with instructions to find somewhere cool to play until lunch was ready. With the sun high in the sky, we’d retreat into the cool and the dark behind the massive hydrangea bush at the bottom of the front stairs. From there we’d peer through the wooden slats at the sloping dirt floor beneath the house.

The door to the shadowy world was padlocked so we had to spy from a distance the hazy piles of mysterious items assembled in the middle: abandoned bicycles and suitcases, an ancient dog cart, and things belonging to the grandfather we’d never met. We knew his name though – Hughie – and we’d seen his picture: the rakish grin, black Irish eyes and old-fashioned suit that gave him a certain glamour, the air of a long-ago movie star. It was strange looking at that mischievous, handsome face, sharing a laugh with the camera, unaware that his end would come too soon.

He used to pick Mum up from evening classes at the high school in Kelvin Grove when she was studying for her Senior, and embarrass her sometimes by making proud declarations to his mates at the Stafford Bowls Club about what a hard worker his girl was. ‘Works all day for the Council and studies for Senior at night,’ he’d say, causing her to smile against her shoulder, wilting under the weight of such public attention.

One night, in the car, she complained about being tired and not liking her work. It wasn’t fair, she said, that she had to do both while her friends were still at school full-time. Without taking his eyes from the road, Hughie put her straight: ‘Do you think I like my job?’ He’d been twelve when one of his brothers arrived at school to fetch him. ‘Come on, mate,’ he’d said. ‘Dad’s hurt his leg and Mum says you gotta come home; it’s time to get a job.’ Hughie drove a delivery van for a small-goods company and if it wasn’t what he’d dreamed of, it was a job and a man’s duty.

He was the sort of dad who took his daughters fishing, laughing when the ‘Billy-Lids’ baulked at threading the mullet-gut on the line. He liked a beer at the bowls club after work and had a habit of singing ‘Galway Bay’ all the way home. In the evenings, he’d sit on the sofa and his girls would take turns on his shoulders, styling his hair with brushes and ribbons, giggling as they tied it up in bows.

He died when Mum was sixteen, on a camping trip at Kingscliff. The aneurism had chased him in his sleep and caught him unawares. His twin sister lived forty years after him, and we wept for both of them at her funeral. The lifetime Hughie had missed, all the cracking Brisbane storms, the coastline left un-fished, the grandchildren who’d have lined up to tie ribbons in his hair. Nana never remarried, but not for lack of offers. She was resolute: it was one thing to be a young man’s darling, she said, but she wasn’t going to be an old man’s slave.

We always ate lunch at Nana’s table in the centre of the kitchen. It had started its life as an art deco wooden piece but disappeared one morning in the late fifties to be returned, rather mysteriously, a week later, outfitted for the new decade: a red laminex top with chrome edging, the square wooden legs replaced by cream metal cylinders and black rubber feet. It was the same table Mum had been sitting at in the early sixties, when her big sister came running home from a friend’s house and produced a mysterious white bulb. ‘It’s garlic,’ she’d told her stunned audience. ‘The Italians cook with it. It’s just like onion but you hardly need to use any.’

Not that Nana used garlic when she made lunch for us. We had roast chicken and potatoes, with peas she’d shelled herself, followed by jelly and two fruits. And there was always lemonade to drink. When Nana knew we were coming, she’d walk the two kilometres to the shops on Stafford Road, returning with a string bag full of canned fizzy drinks with which to spoil us.

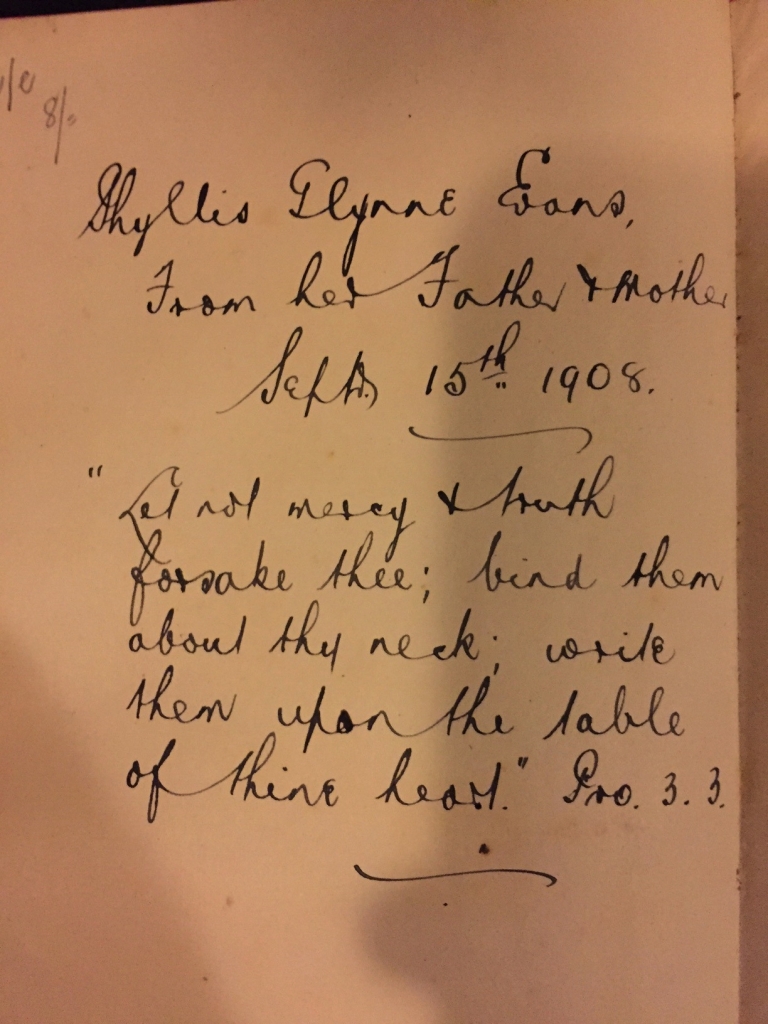

After lunch, I would escape to the spare room, where a narrow bookshelf bowed under the weight of precious volumes that Mum and her sisters had collected when they were girls. School Friend and Girls’ Crystal annuals from every year in the 1960s, a different sister’s name on each title page. I used to trace my finger over my mum’s name (the one from before she got married and became my mum) and the sketchy portraits drawn in biro, her sure, artist’s hand evident even then. The same style, the same doodled faces that adorned the backs of envelopes at our home in the mountains.

On rare occasions, we were allowed to ‘rest’ in Nana’s room. The blue chenille bedspread, home to the dolly with an empty neapolitan ice-cream tub beneath her crocheted skirt, was always perfectly smooth, and the grey laminex dressing table housed a colourful array of bijou necklaces, bangles, and earrings, the sort Ava Gardener wore in the black-and-white films we watched sometimes with Nana in the afternoons. There was a powder puff, too, sitting in a bowl of musky talcum on top of a lace doily, and wedding photos of our aunts wearing beehive hairdos and very short dresses, and one of our mum and dad. ‘We were dead then,’ my sister said solemnly, as we gazed at their smiling faces.

A lot seemed to have happened when we were dead. We caught the threads of stories and embroidered the details ourselves. I daydreamed about the night Nana was caught dancing with an American soldier on the footpath outside a café on St Paul’s Terrace by her stern Parliamentarian father; the childhood teasing of her little cousin, Jackie, under whose chair she threw her lunch crusts, and who she made pull her about the Spring Hill garden in the little dog-cart; Hughie’s large Irish family and their childhood in Windsor, the nick- names they had for one another (his was Brewster-Toddles); and the night he and Nana met and fell in love, when one of her sisters brought him home to meet the family.

When dusk fell and the visit was almost over, we’d pile into Nana’s pink tub. They were always lovely deep baths (a rare privilege for us mountain kids) because Nana was on town water. The soap smelled of oats and our nighties felt different just for being worn in a new place. While Mum loaded the car, my sisters and I knelt side-by-side on the edge of the armchair and peered through the aluminium blinds at the twinkling suburbs, rippling towards the night-time city. Views weren’t the privilege of the wealthy then, and we thought it looked like Fairyland, or Oz, glittering in the distance.

A kiss on Nana’s papery cheek, and we folded ourselves into the back seat of our Triumph, ready to leave Brisbane and all its exotic sights and sounds. And, as we drove away, we watched through the rear window, the single dainty figure beneath the humming porch light, becoming smaller and smaller as she waved at us, before disappearing again inside her house on the Stafford slopes.

Kate Morton, Brisbane, 2009