I was contacting my six-year-old son’s schoolbooks over the weekend and by complete coincidence my mum arrived with an enormous sack of musty, dusty old books that had been mine when I was around the same age. They’d turned up in a cupboard on Tamborine Mountain and she thought that I should have them.

There were a number of things inside that sack that I’d completely forgotten: it may interest you to know, for instance, that my social studies scrapbook from the mid 1980s contains a brief unit on ‘Head lice and how to get rid of them’, complete with a six step illustrated guide. For your edification, step two, ‘Use special shampoo twice in one week’, is underlined, so I gather that part’s rather important. Such useful personal grooming tips can be found sprinkled amongst units as diverse as ‘How to make a light bulb light up’ and ‘I could help a disabled person this way’. I’ve listed ten ways to help disabled people, but I’ve asterisked and underlined number seven, ‘Be Nice.’ Which seems like pretty good advice when dealing with people in general.

I couldn’t help wondering how my dad felt about the little essay I wrote about him:

“My father’s name is Warren. He is about forty-six years old. [Dad was 34 at the time.] He is an engineer. He likes beer, picnics, and watching the news.”

It’s illustrated, and he’s looking up from the television set to smile. The teacher has given me a ‘Very Good’ stamp and added, ‘Well written! Neat work!’ I have made a mental note to check my son’s parental essays before they go back to school for marking (of him) and judgement (of me).

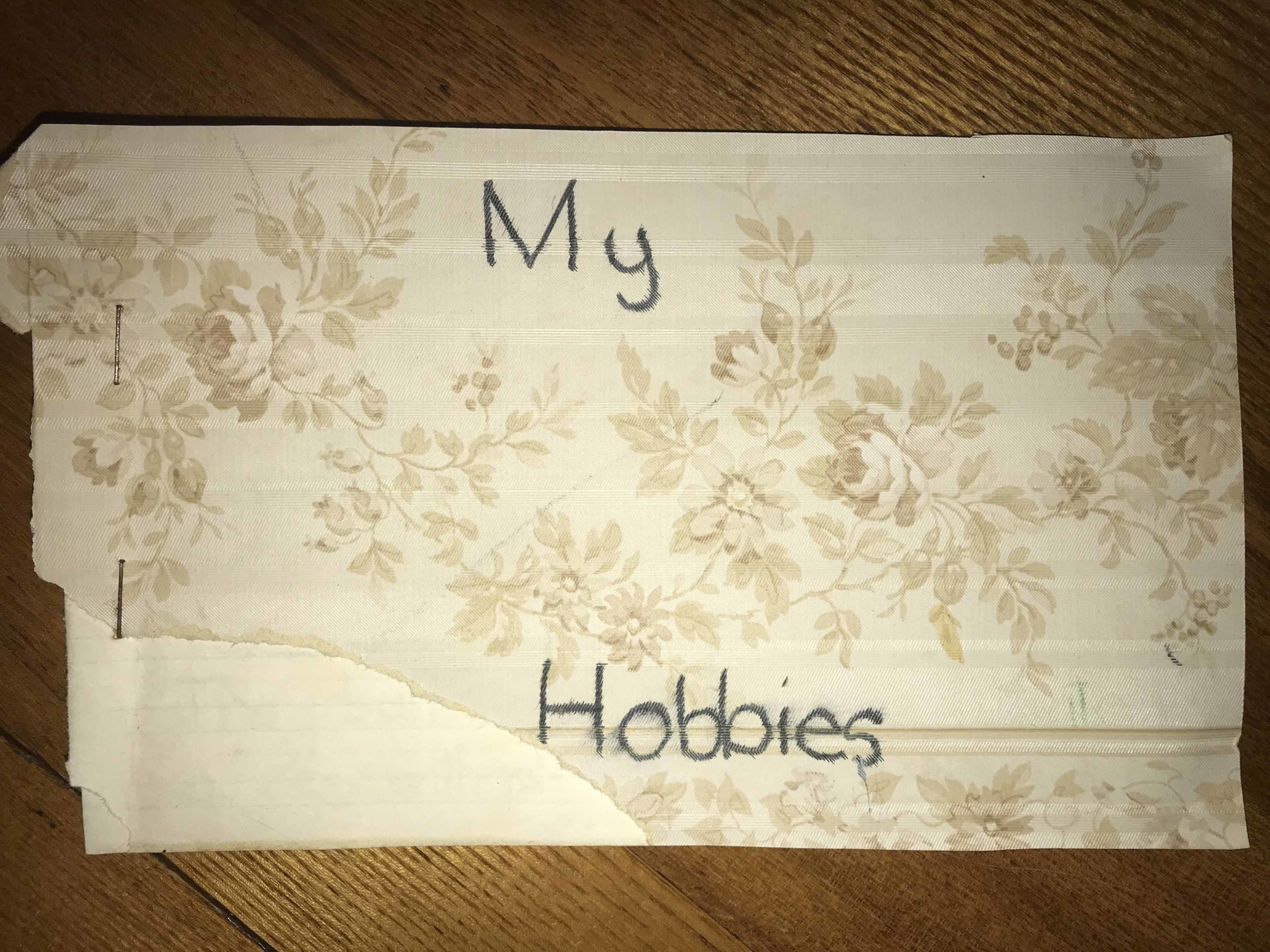

My favourite find was a little book, hand-cut and stapled by the teacher, its cover made from brown swirly floral wallpaper, circa 1979. I remember being rather awed by that wallpaper cover: it had a lustre to it back then, so the brown was almost golden. The passing decades have stripped it to matte, but I still felt an echo of reverence as I held it in my hands. We were not a wallpaper family, and I always felt a bit envious of those who were. On the front of my special book, I’ve printed the title ‘My Hobbies’, and inside, in very careful handwriting, I’ve written that my hobby is being a ballerina and then outlined in great detail the times and days that I attend ballet lessons. And clarinet lessons. And then the possible contingencies in case I couldn’t make one of those lessons and needed to make it up.

On the final page, I came across the following:

As I went through those books, alongside the things that had slipped my memory completely, were certain pages I remembered vividly. As in, where I’d been sitting when I’d worked on them, mistakes I’d made and how I felt about them, bits that made me proud. The distance between now and then was missing, somehow, and I was able, almost, to reach out and touch my seven-year-old self. I don’t need much urging to think about memory and the way it ties us to the past, and I’ve been wondering what it is about some experiences that makes them so easily retrievable. Traumatic or exciting events I can understand: but why remember the moment spent sitting at the kitchen bench, eating sultanas and shading around the illustration of a girl having her hair combed for lice, when so many other similar moments are lost?

And, when I’d returned to covering school books, and I was doing that thing with the ruler that gets the bubbles out of the contact, I had the happy-but-also-melancholy wondering as to whether my son, decades from now, will pull out the notebooks that his mum covered for him, dust them off, and turn their pages once more. What will he have written or drawn inside? Will he look back at the copious drawings of A380 planes and remember his dream of being a pilot? Will he perhaps be a pilot? And will there be certain pages that draw him, as if by a thread, back to the moment when he sat, six years old, in a damp classroom, and the days seemed to stretch eternally, and his lunch was waiting for him in his bag, and the future seemed endless? I hope so.

Brisbane, 2010